The Temples of Pompeii constitute a fundamental religious site within the city’s archaeological complex, offering a vision of Roman devotion. Here we detail the structures that integrate the UNESCO World Heritage site and represent the architectural and spiritual evolution of a city frozen in time.

Pompeii was home to approximately more than 10 sacred sites, among which the Temple of Apollo, the Capitolium, the Temple of Isis, and the Temple of Venus stand out. These structures were distributed between the Forum, the Gladiators’ Triangular Forum, and various residential areas, functioning as hubs for political and social life:

The buildings span historical periods ranging from the Archaic Period in the 6th century BC, with initial Greek and Etruscan influences, through the Samnite era, to the Roman Republican Period and finally the Roman Imperial Period in the 1st century AD. The architecture reflects the successive phases of expansion and the changes in city administration after becoming a Roman colony.

The religious ensemble serves as evidence of a simultaneous cult to Greek, Roman, and Egyptian deities in a single urban center. This coexistence of gods, such as Apollo, Jupiter, and Isis, demonstrates the cultural diversity of Pompeii and the integration of foreign rites into the Roman civic fabric

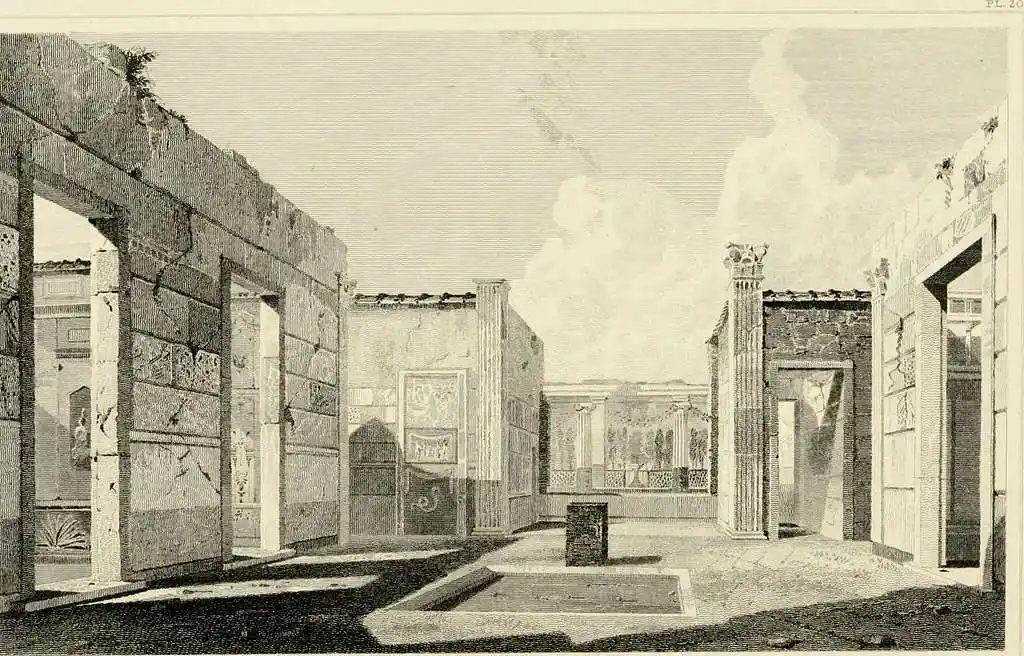

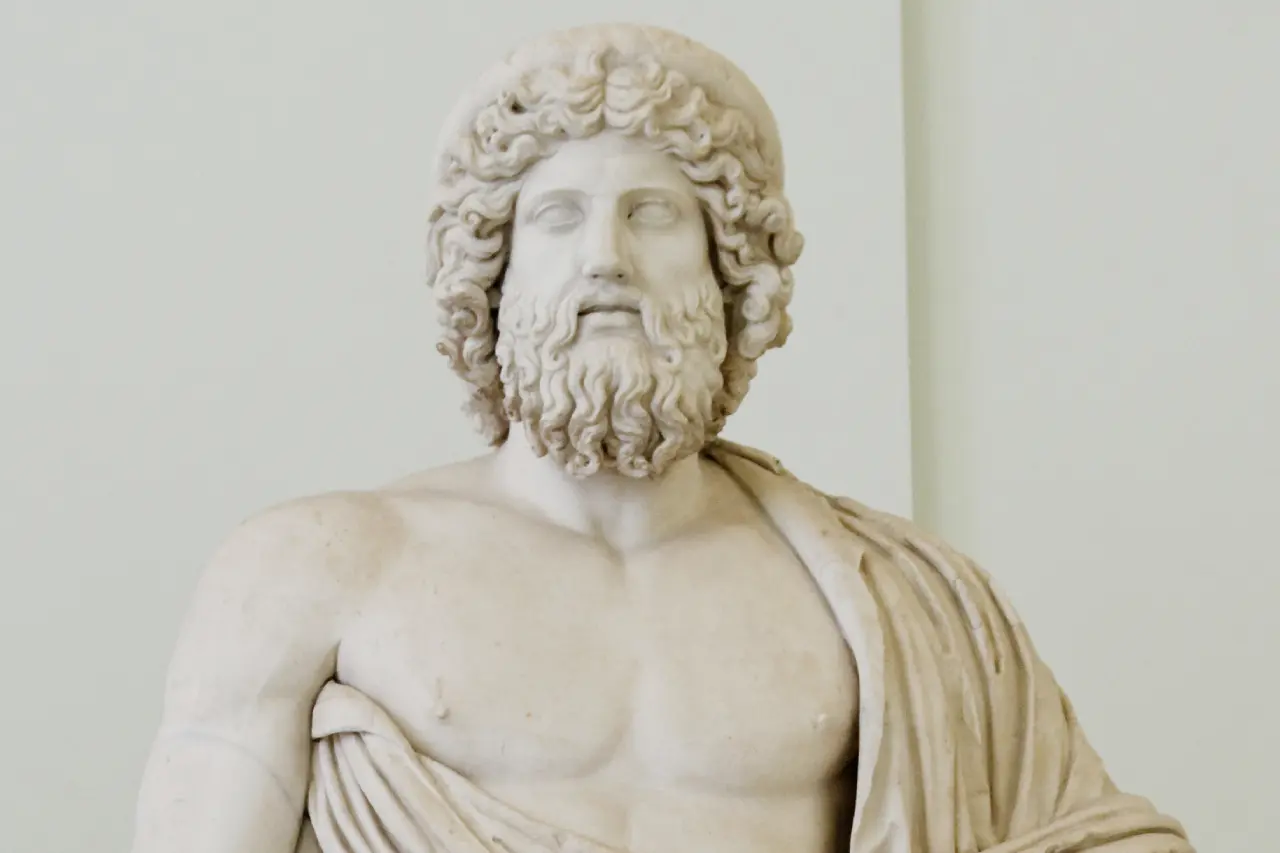

The Temple of Apollo, originally built in the 6th century BC and remodeled in the 2nd century BC, served as the main religious center of Pompeii, dedicated to Apollo as a divinity linked to divination, music, and the protection of the city. Settlers of Greek influence erected it, and later inhabitants adapted it during the Samnite period. It stands out for its portico of 48 Ionic columns and for housing Roman copies of bronze statues of Apollo and Diana.

As a curious fact, this enclosure constitutes one of the buildings with the longest chronological sequence in Pompeii, reflecting more than 600 years of religious continuity and transformation.

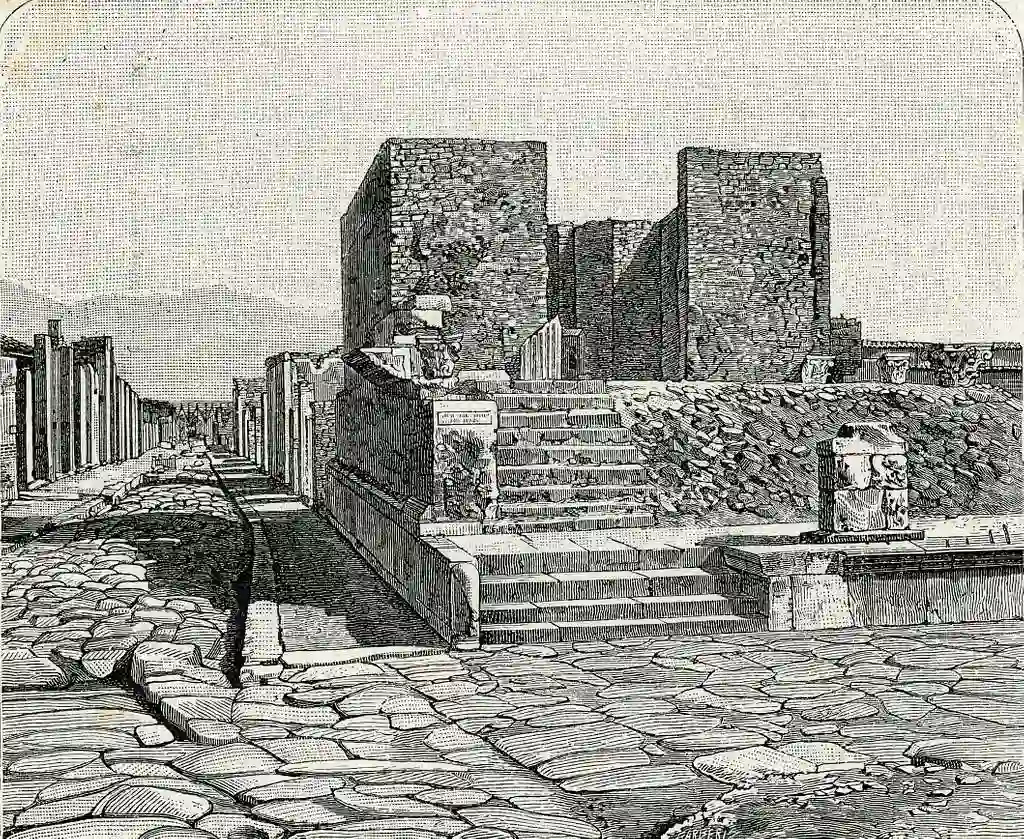

Built at the end of the 2nd century BC and transformed into a Capitolium following the Roman colonization of Pompeii in 80 BC, this temple functioned as a symbol of Rome’s sovereignty and as the seat of the cult of the Capitoline Triad. The authorities of the new colony ordered its monumentalization, providing it with a large frontal staircase and a triple cella that housed a colossal statue of Jupiter, of which only the bust remains today.

Beneath the podium of this Pompeian temple lay favissae, underground chambers intended for depositing and preserving sacred objects and ritual offerings withdrawn from worship.

The Temple of Isis dates back to the 2nd century BC, although the preserved structure corresponds to a reconstruction following the earthquake of 62 AD, dedicated to the mystery cult of the Egyptian goddess. Numerius Popidius Celsinus, a young member of a freedman family, financed the work. Although he was still a child, his participation as a benefactor was a symbolic and legal act promoted by his father, who sought to increase the family’s social prestige in the Roman colony.

Some of the frescoes and statues that were in the temple have been moved to museums, such as the National Archaeological Museum in Naples, where they are kept more securely.

Additionally, a legend claims that Mozart visited this temple in 1770 during his journey through Italy and felt so impressed by its atmosphere and Egyptian decoration that he took inspiration for the set design of his opera The Magic Flute.

Built after 80 BC, the Temple of Venus Pompeiana was dedicated to Venus, protector of the colony and symbol of Roman military success. Roman colonists loyal to Lucius Cornelius Sulla, the Roman dictator who reorganized Pompeii as a colony after the Social War, erected it. They decorated it with luxurious marble coverings on a terrace facing the sea, making it a visible landmark from the city and the port.

Despite being one of the most sumptuous temples in Pompeii, it was reduced to its foundations by 79 AD, as the repairs following the earthquake of 62 AD were never completed. Today, only archaeological remains allow one to imagine its ancient magnificence.

This enclosure was built in the 1st century AD, during the reign of Emperor Augustus, with the aim of paying cult to the deity Fortuna (goddess of chance, good luck, and prosperity) and the imperial family, strengthening propaganda and loyalty toward the emperor.

The local magistrate Marcus Tullius, belonging to Pompeii’s elite, funded the work entirely, equipping it with interior niches containing statues of the imperial family and a central figure of the deity carrying a rudder and a cornucopia—symbols of destiny and prosperity. Marcus Tullius decided to erect the temple on his private property, using this sacred space as a tool for personal prestige and a demonstration of loyalty to the emperor.

Today, only archaeological remains of the temple are preserved, allowing for the identification of its location. The interior decoration and original statues have been lost.

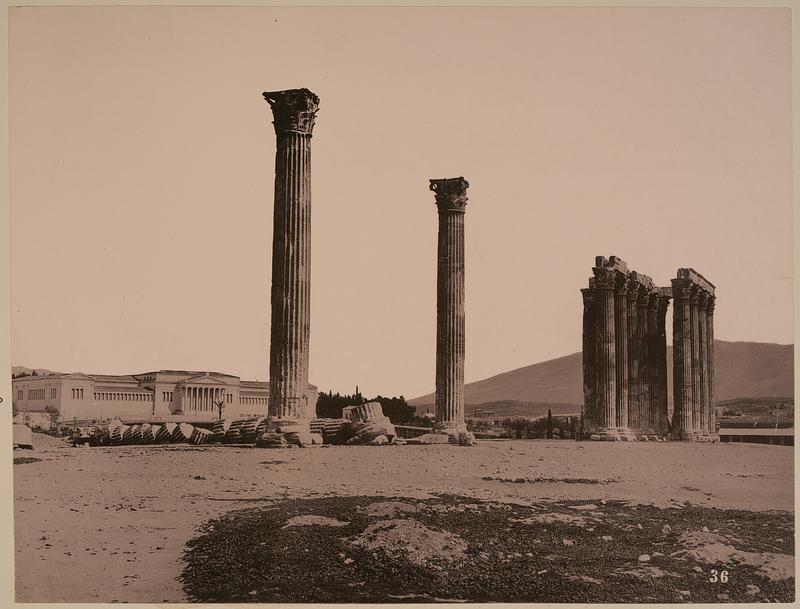

The Doric Temple is a 6th-century BC structure dedicated to the cult of Hercules, the mythical founder of the region, and Minerva, the Roman goddess of wisdom and strategy. Archaic Greek colonists built it following the canons of their original architecture, from which massive Doric capitals and fragments of terracotta decorations are preserved.

For the inhabitants of Pompeii in the 1st century BC, this temple was already considered a historical antiquity, and they preserved it as a monument to their Greek roots rather than modernizing it according to the Roman standards of the time.

This small sanctuary, dating to the end of the 3rd century BC, functioned as a place of healing dedicated to Asclepius, the Greek god of medicine and healing. However, after Romanization, it also incorporated the cult of Jupiter Meilichios, a Roman form of Jupiter linked with protection and the atonement of evils. Samnite elites built it, and it stood out for its volcanic tuff altar and terracotta statues representing deities related to health.

It is one of the smallest temples in Pompeii, strategically located near the theater district, facilitating the arrival of those who came to the sanctuary in search of spiritual and physical healing.

The Temple of the Genius of Augustus was erected at the beginning of the 1st century AD to pay cult to the vital force or “Genius” of the reigning emperor. Built in a highly visible area near the Forum, it stands out for the marble altar that is still preserved, decorated with reliefs representing the sacrifice of a bull in honor of the emperor.

Originally dedicated to the Genius Augustus, this temple was later associated with the cult of Emperor Vespasian, which is why it is also known as the Temple of Vespasian, reflecting its historical evolution and continued use as a space for imperial propaganda.

The temple also served as a meeting point for freedmen, who saw the imperial cult as a way to achieve social recognition and demonstrate their loyalty to Roman power.

Built after the earthquake of 62 AD on the east side of the Forum, this sanctuary was dedicated to the protective gods of the city. The municipal council of Pompeii built it as an act of atonement to seek divine protection after the natural disaster.

The structure was characterized by its open design, with large niches for statues and a colored marble pavement, although today only archaeological remains allow for the inference of these characteristics. A curious fact is that its diaphanous design allowed citizens in the Forum to observe the rites and images of the gods from any point outside the enclosure.

Distributed throughout the city since the 1st century BC, these altars served the cult of the Lares Compitales, the gods who protected crossroads and neighborhoods. Local communities and the enslaved people of each neighborhood built and maintained them. They featured simple frescoes showing priests making offerings on an altar.

It is important to clarify that these are not temples in a strict architectural sense, but rather points of popular worship. A curious fact is that these altars were the epicenter of the Compitalia festivals, the only time of year when enslaved people enjoyed a certain degree of freedom and prominence in public life.

The evolution of Pompeii’s temples reflects the political, cultural, and social transformation of the city over the centuries:

The city of Pompeii underwent a severe structural crisis before its disappearance. The earthquake damage 62AD caused a violent upheaval across the Campania region, leading to the collapse of numerous public buildings, temples, and homes. This seismic event severely weakened the city’s infrastructure, leaving much of its urban fabric in a state of ruin and setting the stage for the final catastrophe.

Seventeen years later, when the Eruption of Mount Vesuvius occurred in 79 AD, many of the main temples were still under construction or half-ruined. Repair work had not been completed due to the sheer magnitude of the initial destruction. The Temple of Jupiter, the center of state religious life, and the Temple of Venus, patroness of the city, are clear examples of these incomplete projects; both featured structural scars or scaffolding at the moment of the volcanic disaster. In contrast, the Temple of Isis was restored quickly through private patronage, allowing it to remain operational while the official sanctuaries still bore the marks of the earlier disaster.

The Temple of Apollo and the Doric Temple are the oldest, both dating from the 6th century BC, during the period of initial Greek influence in the region.

In addition to the temples, some things to see in Pompeii are the Amphitheater, the Forum Baths, the Villa of the Mysteries, and the Lupanar stand out. These sites offer a complete perspective of Roman daily life.

The cult of Apollo in Pompeii was influenced by the Greek rites associated with the Oracle of Delphi (the most important religious center in ancient Greece dedicated to this god). In Delphi, a priestess named Pythia uttered prophecies inspired by Apollo, which priests interpreted to guide political, military, and personal decisions. Similarly, the practice of prophecy and divination occurred in Pompeii, allowing citizens to communicate spiritually with the god and seek his protection and guidance.

The abundance of temples stems from the cultural diversity of its inhabitants and the need to legitimize political power through public religion and the imperial cult.

Yes, it is possible to visit the main temples in a single day, although it requires rigorous planning. The temples located in the Forum (such as the Capitolium, the Temple of Venus Pompeiana, and the Temple of the Genius of Augustus) can be toured relatively quickly. Conversely, minor sanctuaries and altars scattered throughout the city require more time and travel due to their location outside the central core.

POMPEII TICKETS

With a reserved admission ticket, visit Pompeii, a UNESCO World Heritage site. As you take your time exploring the archaeological site… see more

TOURIST INFORMATION

Pompeii welcomes visitors throughout the year with varying schedules to accommodate the changing seasons. From April 1st to October… see more

POMPEII INFORMATION

The Pompeii historical site offers a unique glimpse into the life of an ancient Roman city, preserved through time by the volcanic ash… see more